Michael Kimmelman writes:

That the Francis Bacon retrospective at Tate Britain has been mobbed should surprise nobody.

The show is a landmark, a knockout, and its timing turns out to be nearly perfect.

Photo: Adrian Dennis/Agence France-Presse

Sixteen years have passed since the Irish-born Bacon died, at 82,

during which the art world has radically changed. He suddenly looks fresh.

Photo: Estate of Francis Bacon/VAGA, New York

How so? Late in life, he became, contrary to his sensational art,

a sort of old-school gentleman, chivalrous and immensely kind

when he wished to be, reticent otherwise, a monument of postwar Britain.

Photo: Estate of Francis Bacon/VAGA, New York

By his late 70s, Bacon had come to seem something of a throwback;

it was widely said his best work was behind him.

Photo: Estate of Francis Bacon/VAGA, New York

But since then historians have mined the sources from which Bacon cribbed images

and opened up the crucial subject of gay sexuality in his work,

and this, along with his bad-boy reputation, has made him a source of steady fascination.

Most important, with the breathing space of a little time,

it’s become obvious how pure a painter he was, not just early on.

Photo: Estate of Francis Bacon/VAGA, New York

Cunning and self-conscious, glad to outrage, with the delicacy of those blurry

but somehow distinct faces and electric palette, conjuring up Carnaby Street,

his work translates quite easily to a new century.

Photo: Estate of Francis Bacon

Old School Bad Boy’s Messy World

LONDON — That the Francis Bacon retrospective here at Tate Britain has been mobbed since opening several days ago should surprise nobody. The show is a landmark, a knockout, and its timing turns out to be nearly perfect.

Sixteen years have passed since the Irish-born Bacon died, at 82, during which the art world has radically changed, and the generation of Americans weaned on postwar abstraction and congenitally skeptical of Bacon is being gradually displaced. The other day there were dozens of young art students, not a few of them sketching, in front of the pictures. I suspect the same will happen when the show, judiciously organized by Matthew Gale and Chris Stephens, lands in Madrid, then New York. Bacon suddenly looks fresh.

How so? Late in life, it’s true, he became, contrary to his sensational art, a sort of old-school gentleman, chivalrous and immensely kind when he wished to be, reticent otherwise, a monument of postwar Britain who, for a curious guest, would rehearse the old lines and visit old haunts like the Colony Room, the run-down drinking club where he paid for bottles of Champagne from a thick wad of cash he kept rolled up, à la Al Capone, in a pocket of his suit. (The ill-fitting suits, long after he could afford Savile Row, came from a neighborhood tailor to whom, typical of Bacon, he remained loyal.)

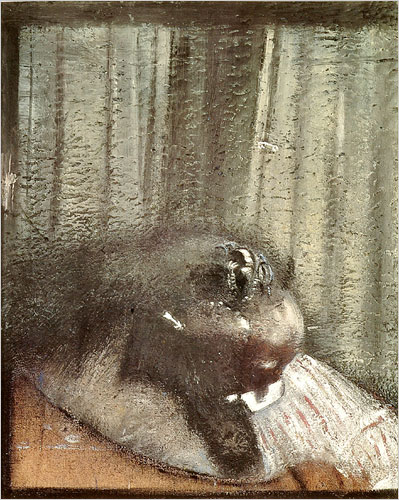

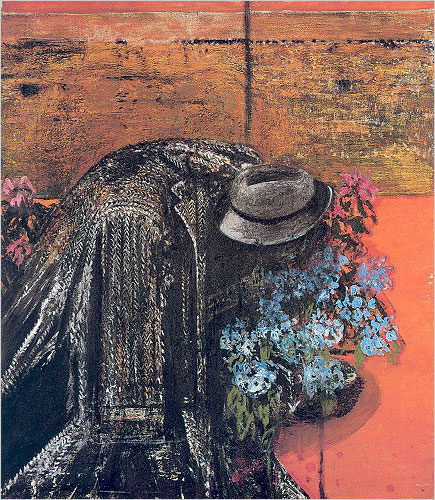

“Figure Study I,”

a work in the Francis Bacon retrospective through Jan. 4 at Tate Britain in London.

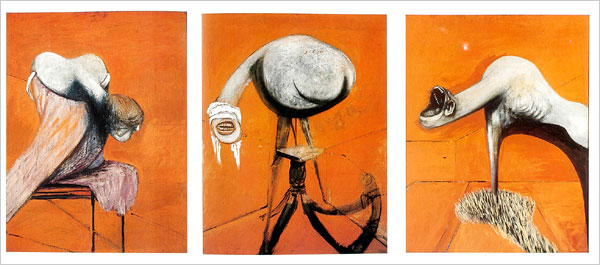

In those days he was painting works like a second version of the triptych “Three Studies for Figures at the Base of a Crucifixion,” the original of which in the mid-1940s had confronted a battered, convalescent nation with what’s commonly called the shock of recognition. Now he was remaking the work, as his friend the painter Lawrence Gowing put it about late Bacon generally, to look more “classically serene.”

“I’m an optimist, but about nothing,” Bacon kept repeating, while lamenting his old age as “a disease, a desert, because all one’s friends die.” He loved to quote Yeats and Proust and T. S. Eliot and remained enmeshed in what Michael Leja, an American art historian, has in a different context called “Modern Man discourse” — a serious hand-me-down passel of existentialism and other philosophy from the 1940s and ’50s, popularized, as David Alan Mellor writes in an essay in the show’s excellent catalog, by the claustrophobic spaces of film noir. This netherworld of dingy hallways and shuttered rooms had long been the arena of Bacon’s art.

So in various respects, by his late 70s, Bacon had come to seem something of a throwback; it was widely said his best work was behind him. But since then historians have mined the sources from which he cribbed images and opened up the crucial subject of gay sexuality in his work, which was long repressed, and this, along with his bad-boy reputation, which never goes out of fashion, has made him a source of steady fascination, never mind the lurid films and biographies and the admiration of art-world celebrities like Damien Hirst. Most important, with the breathing space of a little time, it’s become obvious how pure a painter he was, not just early on.

His repertory — “brand” would be the word Mr. Hirst might use — of bloody carcasses and monsters; the mutilated, decomposing heads with immaculate teeth; the mangy dogs and screaming popes and salary men, silent and watchful, caged like zoo animals, then enclosed behind the gold frames and reflective glass, in which we too appear like ghosts: it’s all already there in his work by the mid-1950s.

So is the touch. In “Figure Study I” or “Head II,” from the ’40s, the surfaces are busy and dense like stucco or tweed, or thick as an elephant’s hide, but with exquisite veils on top — a mix of roughness and fragility, aggression and sensuality that would define the work across the career. Bacon also swiped thin washes of purple, black and white over what looks like raw canvas to paint his first pope, fussing the gaping mouth, creepily. Spectral hints of gold brocade, refined like Chinese calligraphy, glimmer in the ether.

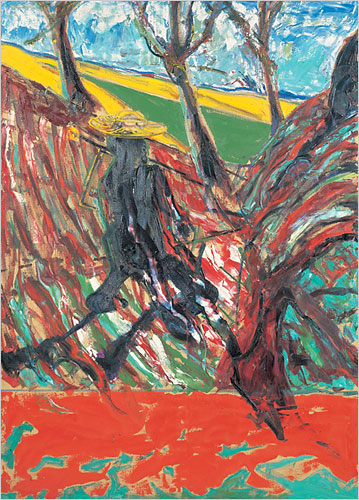

Elsewhere beefy men wrestle and dive into pools of blue-black nothingness. Against high-key fields of red and orange, half-animal, half-human blobs recline like patients on an operating table or they melt and evaporate. Bacon traveled during the late ’50s to Tangier, absorbing local color, allowing his technique to loosen, producing “Study for a Portrait of van Gogh VI,” a clangorous mass of red and green, improbably successful, and he painted a few messes too, like “Figure in a Mountain.”

Out of all of that came, by the ’70s and ’80s, we can see in the Tate show, yet more complex architecture, a widened palette, and a calculated willingness to risk failure. Within the narrow terrain he mapped at the start, with its melancholy and blend of private with literary iconography, Bacon didn’t just repeat himself.

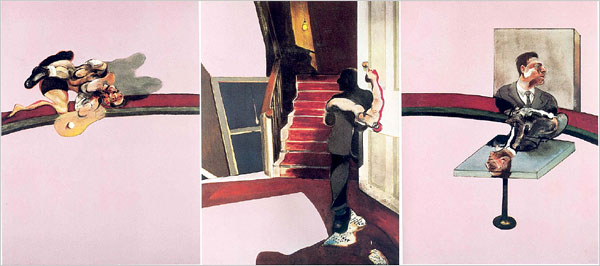

Several triptychs and portraits, reflecting on the suicide of his companion George Dyer in 1971, mark a clear experiment in conflicted sentiment; they’re heartbreaking but simultaneously clinical. As a friend of Bacon’s, the editor Nikos Stangos, once put it, Bacon “never expressed moral indignation about anything.” That in a nutshell explains the work’s ruthless elegance.

Some really appalling late pictures, like a large triptych from 1976, which some squillionaire recently paid a fortune to buy, look horribly overstuffed with ugly heads and tired gimmicks, as if Bacon, worried he had exhausted the empty stretches of color he so often painted, didn’t know when to stop filling the canvas up. Whether, during these last decades, he came merely to parody himself, painting too slickly, is the only real subject of debate the exhibition has aroused. The answer is, yes, sometimes he did.

All the same, he made, out of the blue, “Jet of Water,” a great ejaculation of splashed white pigment, which looks stunning. Despite his blindness to pure abstraction — which, having a tendency toward decorativeness, he feared led only to empty gesture — he devised a Rothko-like picture, sinister and wry, called “Blood on Pavement.” Even the second version of that early triptych of figures at the base of a crucifixion turns out to have its own eloquence, almost daring a viewer to find it too beautiful.

Cunning and self-conscious, glad to outrage, with the delicacy of those blurry but somehow distinct faces and electric palette, conjuring up Carnaby Street, his work translates quite easily to a new century. So does the sweaty sex and violence, luxuriant but couched in aloofness and girded, always, by grand allusions to old masters and learned texts.

Karl Georg Büchner, the 19th-century German playwright, speaking of which, once asked a question that Bacon must have come across. “How,” Büchner inquired, “can you not hear the terrible screams all around that we call silence?”

Through the popes and Willy Lomans and so much else that Bacon painted, they make this exhibition sing.

http://www.nytimes.com/2008/09/25/arts/design/25abroad.html?th&emc=th

Notes

Francis Bacon (28 October 1909 – 28 April 1992) was an Irish-born British figurative painter.

He was a collateral descendant of the Elizabethan philosopher Francis Bacon.

His artwork is known for its bold, austere, and often grotesque or nightmarish imagery.

A major retrospective of Bacon's work opened on 11 September 2008 at Tate Britain, London.

It is billed as the largest retrospective of his work ever mounted, containing around sixty of his works.

In January 2009, it will travel on first to the Prado Gallery in Madrid, Spain,

and then the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York, "where it will end in the summer of 2009."

'Blue > e—art—museum' 카테고리의 다른 글

| Celebrating Past and Future of Korea - LACMA Late Night Event (0) | 2009.09.10 |

|---|---|

| Art of the Korean Renaissance 1400-1600 한국 르네상스시대의 예술 (0) | 2009.04.05 |

| Harald Sohlberg (0) | 2008.09.09 |

| Nothing can restrict Fine Art no rules painting (0) | 2008.08.06 |

| Attraction of Man with Art (0) | 2008.08.02 |