Chapter

Chapter

One

The End

This

is a story about a man named Eddie and it begins at the end, with Eddie

dying in the sun. It might seem strange to start a story with an ending. But all

endings are also beginnings. We just don't know it at the time.

The

last hour of Eddie's life

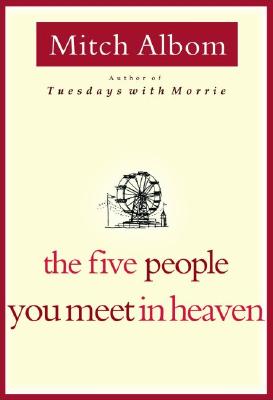

was spent, like most of the others, at Ruby Pier, an amusement park by a great

gray ocean. The park had the usual attractions, a boardwalk, a Ferris wheel,

roller coasters, bumper cars, a taffy stand, and an arcade where you could shoot

streams of water into a clown's mouth. It also had a big new ride called

Freddy's Free Fall, and this would be where Eddie would be killed, in an

accident that would make newspapers around the state.

At

the time of his death, Eddie

was a squat, white-haired old man, with a short neck, a barrel chest, thick

forearms, and a faded army tattoo on his right shoulder. His legs were thin and

veined now, and his left knee, wounded in the war, was ruined by arthritis. He

used a cane to get around. His face was broad and craggy from the sun, with

salty whiskers and a lower jaw that protruded slightly, making him look prouder

than he felt. He kept a cigarette behind his left ear and a ring of keys hooked

to his belt. He wore rubber-soled shoes. He wore an old linen cap. His pale

brown uniform suggested a workingman, and a workingman he was.

Eddie's

job was "maintaining"

the rides, which really meant keeping them safe. Every afternoon, he walked the

park, checking on each attraction, from the Tilt-A-Whirl to the Pipeline Plunge.

He looked for broken boards, loose bolts, worn-out steel. Sometimes he would

stop, his eyes glazing over, and people walking past thought something was

wrong. But he was listening, that's all. After all these years he could hear

trouble, he said, in the spits and stutters and thrumming of the equipment.

With

50 minutes left on earth, Eddie took his last walk along Ruby Pier. He

passed an elderly couple.

"Folks," he mumbled,

touching his cap.

They nodded politely.

Customers knew Eddie. At least the regular ones did. They saw him summer after

summer, one of those faces you associate with a place. His work shirt had a

patch on the chest that read Eddie

above the word Maintenance, and

sometimes they would say, "Hiya, Eddie Maintenance," although he never

thought that was funny.

Today, it so happened, was

Eddie's birthday, his 83rd. A doctor, last week, had told him he had shingles.

Shingles? Eddie didn't even know what they were. once, he had been strong

enough to lift a carousel horse in each arm. That was a long time ago.

"Eddie!"

. . . "Take me, Eddie!" . . . "Take me!"

Forty minutes until his

death. Eddie made his way to the front of the roller coaster line. He rode every

attraction at least once a week, to be certain the brakes and steering were

solid. Today was coaster day -- the "Ghoster Coaster" they called this one

-- and the kids who knew Eddie yelled to get in the cart with him.

Children liked Eddie. Not

teenagers. Teenagers gave him headaches. Over the years, Eddie figured he'd

seen every sort of do-nothing, snarl-at-you teenager there was. But children

were different. Children looked at Eddie -- who, with his protruding lower jaw,

always seemed to be grinning, like a dolphin -- and they trusted him. They drew

in like cold hands to a fire. They hugged his leg. They played with his keys.

Eddie mostly grunted, never saying much. He figured it was because he didn't

say much that they liked him.

Now Eddie tapped two little

boys with backward baseball caps. They raced to the cart and tumbled in. Eddie

handed his cane to the ride attendant and slowly lowered himself between the

two.

"Here we go . . . . Here

we go! . . . " one boy squealed, as the other pulled Eddie's arm around

his shoulder. Eddie lowered the lap bar and clack-clack-clack, up they

went.

A

story went around about

Eddie. When he was a boy, growing up by this very same pier, he got in an alley

fight. Five kids from Pitkin Avenue had cornered his brother, Joe, and were

about to give him a beating. Eddie was a block away, on a stoop, eating a

sandwich. He heard his brother scream. He ran to the alley, grabbed a garbage

can lid, and sent two boys to the hospital.

After that, Joe didn't

talk to him for months. He was ashamed. Joe was the oldest, the firstborn, but

it was Eddie who did the fighting.

"Can

we go again, Eddie? Please?"

Thirty-four minutes to

live. Eddie lifted the lap bar, gave each boy a sucking candy, retrieved his

cane, then limped to the maintenance shop to cool down from the summer heat. Had

he known his death was imminent, he might have gone somewhere else. Instead, he

did what we all do. He went about his dull routine as if all the days in the

world were still to come.

One of the shop workers, a

lanky, bony-cheeked young man named Dominguez, was by the solvent sink, wiping

grease off a wheel.

"Yo, Eddie," he said.

"Dom," Eddie said.

The shop smelled like

sawdust. It was dark and cramped with a low ceiling and pegboard walls that held

drills and saws and hammers. Skeleton parts of fun park rides were everywhere:

compressors, engines, belts, lightbulbs, the top of a pirate's head. Stacked

against one wall were coffee cans of nails and screws, and stacked against

another wall were endless tubs of grease.

Greasing a track, Eddie

would say, required no more brains than washing a dish; the only difference was

you got dirtier as you did it, not cleaner. And that was the sort of work that

Eddie did: spread grease, adjusted brakes, tightened bolts, checked electrical

panels. Many times he had longed to leave this place, find different work, build

another kind of life. But the war came. His plans never worked out. In time, he

found himself graying and wearing looser pants and in a state of weary

acceptance, that this was who he was and who he would always be, a man with sand

in his shoes in a world of mechanical laughter and grilled frankfurters. Like

his father before him, like the patch on his shirt, Eddie was maintenance -- the

head of maintenance -- or as the kids sometimes called him, "the ride man at

Ruby Pier."

Thirty

minutes left.

"Hey, happy birthday, I

hear," Dominguez said.

Eddie grunted.

"No party or nothing?"

Eddie looked at him as if

he were crazy. For a moment he thought how strange it was to be growing old in a

place that smelled of cotton candy.

"Well, remember, Eddie, I'm off

next week, starting Monday. Going to Mexico."

Eddie nodded, and Dominguez

did a little dance.

"Me and Theresa. Gonna

see the whole family. Par-r-r-ty."

He stopped dancing when he

noticed Eddie staring.

"You ever been?"

Dominguez said.

"Been?"

"To Mexico?"

Eddie exhaled through his

nose. "Kid, I never been anywhere I wasn't shipped to with a rifle."

He watched Dominguez return

to the sink. He thought for a moment. Then he took a small wad of bills from his

pocket and removed the only twenties he had, two of them. He held them out.

"Get your wife something

nice," Eddie said.

Dominguez regarded the

money, broke into a huge smile, and said, "C'mon, man. You sure?"

Eddie pushed the money into

Dominguez's palm. Then he walked out back to the storage area. A small "fishing hole" had been cut into the boardwalk planks years ago, and Eddie

lifted the plastic cap. He tugged on a nylon line that dropped 80 feet to the

sea. A piece of bologna was still attached.

"We catch anything?"

Dominguez yelled. "Tell me we caught something!"

Eddie wondered how the guy

could be so optimistic. There was never anything on that line.

one day," Dominguez

yelled, "we're gonna get a halibut!"

"Yep," Eddie mumbled,

although he knew you could never pull a fish that big through a hole that small.

Twenty-six

minutes to live. Eddie

crossed the boardwalk to the south end. Business was slow. The girl behind the

taffy counter was leaning on her elbows, popping her gum.

Once, Ruby Pier was the

place to go in the summer. It had elephants and fireworks and marathon dance

contests. But people didn't go to ocean piers much anymore; they went to theme

parks where you paid $75 a ticket and had your photo taken with a giant

furry character.

Eddie limped past the

bumper cars and fixed his eyes on a group of teenagers leaning over the railing.

Great, he told himself. Just what I need.

"Off," Eddie said,

tapping the railing with his cane. "C'mon. It's not safe."

The teens glared at him.

The car poles sizzled with electricity, zzzap zzzap sounds.

"It's not safe,"

Eddie repeated.

The teens looked at each

other. one kid, who wore a streak of orange in his hair, sneered at Eddie, then

stepped onto the middle rail.

"Come on, dudes, hit

me!" he yelled, waving at the young drivers. "Hit m --"

Eddie whacked the railing

so hard with his cane he almost snapped it in two. "MOVE IT!"

The teens ran away.

Another

story went around about

Eddie. As a soldier, he had engaged in combat numerous times. He'd been brave.

Even won a medal. But toward the end of his service, he got into a fight with

one of his own men. That's how Eddie was wounded. No one knew what happened to

the other guy.

No one asked.

With

19 minutes left on earth,

Eddie sat for the last time, in an old aluminum beach chair. His short, muscled

arms folded like a seal's flippers across his chest. His legs were red from

the sun, and his left knee still showed scars. In truth, much of Eddie's body

suggested a survived encounter. His fingers were bent at awkward angles, thanks

to numerous fractures from assorted machinery. His nose had been broken several

times in what he called "saloon fights." His broadly jawed face might have

been good-looking once, the way a prizefighter might have looked before he took

too many punches.

Now Eddie just looked

tired. This was his regular spot on the Ruby Pier boardwalk, behind the

Jackrabbit ride, which in the 1980s was the Thunderbolt, which in the 1970s was

the Steel Eel, which in the 1960s was the Lollipop Swings, which in the 1950s

was Laff In The Dark, and which before that was the Stardust Band Shell.

Which was where Eddie met

Marguerite.

Every

life has one true-love

snapshot. For Eddie, it came on a warm September night after a thunderstorm,

when the boardwalk was spongy with water. She wore a yellow cotton dress, with a

pink barrette in her hair. Eddie didn't say much. He was so nervous he felt as

if his tongue were glued to his teeth. They danced to the music of a big band,

Long Legs Delaney and his Everglades Orchestra. He bought her a lemon fizz. She

said she had to go before her parents got angry. But as she walked away, she

turned and waved.

That was the snapshot. For

the rest of his life, whenever he thought of Marguerite, Eddie would see that

moment, her waving over her shoulder, her dark hair falling over one eye, and he

would feel the same arterial burst of love.

That night he came home and

woke his older brother. He told him he'd met the girl he was going to marry.

"Go to sleep,

Eddie," his brother groaned.

Whrrrssssh.

A wave broke on the beach. Eddie coughed up something he did not want to see. He

spat it away.

Whrrssssssh.

He used to think a lot about Marguerite. Not so much now. She was like a wound

beneath an old bandage, and he had grown more used to the bandage.

Whrrssssssh.

What was shingles?

Whrrrsssssh.

Sixteen minutes to live.

No

story sits by itself. Sometimes stories meet at corners and sometimes

they cover one another completely, like stones beneath a river.

The end of Eddie's story

was touched by another seemingly innocent story, months earlier -- a cloudy

night when a young man arrived at Ruby Pier with three of his friends.

The young man, whose name

was Nicky, had just begun driving and was still not comfortable carrying a key

chain. So he removed the single car key and put it in his jacket pocket, then

tied the jacket around his waist.

For the next few hours, he

and his friends rode all the fastest rides: the Flying Falcon, the Splashdown,

Freddy's Free Fall, the Ghoster Coaster.

"Hands in the air!" one

of them yelled.

They threw their hands in

the air.

Later, when it was dark,

they returned to the car lot, exhausted and laughing, drinking beer from brown

paper bags. Nicky reached into his jacket pocket. He fished around. He cursed.

The key was gone.

Fourteen

minutes until his death.

Eddie wiped his brow with a handkerchief. Out on the ocean, diamonds of sunlight

danced on the water, and Eddie stared at their nimble movement. He had not been

right on his feet since the war.

But back at the Stardust

Band Shell with Marguerite -- there Eddie had still been graceful. He closed his

eyes and allowed himself to summon the song that brought them together, the one

Judy Garland sang in that movie. It mixed in his head now with the cacophony of

the crashing waves and children screaming on the rides.

"You made me love you -- "

Whsssshhhh.

" -- do it, I didn't

want to do i -- "

Splllllaaaaashhhhhhh.

" -- me love you -- "

Eeeeeeee!

" -- time you knew it, and all the

-- "

Chhhhewisshhhh.

" -- knew it . . . "

Eddie felt her hands on his

shoulders. He squeezed his eyes tightly, to bring the memory closer.

Twelve

minutes to live.

"'Scuse me."

A young girl, maybe eight

years old, stood before him, blocking his sunlight. She had blonde curls and

wore flip-flops and denim cutoff shorts and a lime green T-shirt with a cartoon

duck on the front. Amy, he thought her name was. Amy or Annie. She'd been here

a lot this summer, although Eddie never saw a mother or father.

"'Scuuuse me," she

said again. "Eddie Maint'nance?"

Eddie sighed. "Just

Eddie," he said.

"Eddie?"

"Um hmm?"

"Can you make me . . ."

She put her hands together

as if praying.

"C'mon, kiddo. I don't have all

day."

"Can you make me an animal? Can

you?"

Eddie looked up, as if he

had to think about it. Then he reached into his shirt pocket and pulled out

three yellow pipe cleaners, which he carried for just this purpose.

"Yesssss!" the little

girl said, slapping her hands.

Eddie began twisting the

pipe cleaners.

"Where's your parents?"

"Riding the rides."

"Without you?"

The girl shrugged. "My mom's with

her boyfriend."

Eddie looked up. Oh.

He bent the pipe cleaners

into several small loops, then twisted the loops around one another. His hands

shook now, so it took longer than it used to, but soon the pipe cleaners

resembled a head, ears, body, and tail.

"A rabbit?" the little

girl said.

Eddie winked.

"Thaaaank you!"

She spun away, lost in that

place where kids don't even know their feet are moving. Eddie wiped his brow

again, then closed his eyes, slumped into the beach chair, and tried to get the

old song back into his head.

A seagull squawked as it

flew overhead.

How

do people choose their final

words? Do they realize their gravity? Are they fated to be wise?

By his 83rd birthday, Eddie

had lost nearly everyone he'd cared about. Some had died young, and some had

been given a chance to grow old before a disease or an accident took them away.

At their funerals, Eddie listened as mourners recalled their final

conversations. "It's as if he knew he was going to die . . . . " some

would say.

Eddie never believed that.

As far as he could tell, when your time came, it came, and that was that. You

might say something smart on your way out, but you might just as easily say

something stupid.

For the record, Eddie's

final words would be "Get back!"

Here

are the sounds of Eddie's

last minutes on earth. Waves crashing. The distant thump of rock music. The

whirring engine of a small biplane, dragging an ad from its tail. And this.

"OH MY GOD! LOOK!"

Eddie felt his eyes dart

beneath his lids. Over the years, he had come to know every noise at Ruby Pier

and could sleep through them all like a lullaby.

This voice was not in the

lullaby.

"OH MY GOD! LOOK!"

Eddie bolted upright. A

woman with fat, dimpled arms was holding a shopping bag and pointing and

screaming. A small crowd gathered around her, their eyes to the skies.

Eddie saw it immediately.

Atop Freddy's Free Fall, the new "tower drop" attraction, one of the carts

was tilted at an angle, as if trying to dump its cargo. Four passengers, two

men, two women, held only by a safety bar, were grabbing frantically at anything

they could.

"OH MY GOD!" the fat woman yelled.

"Those people! They're gonna fall!"

A voice squawked from the

radio on Eddie's belt. "Eddie! Eddie!"

He pressed the button. "I see it!

Get security!"

People ran up from the

beach, pointing as if they had practiced this drill. Look! Up in the sky! An

amusement ride turned evil! Eddie grabbed his cane and clomped to the safety

fence around the platform base, his wad of keys jangling against his hip. His

heart was racing.

Freddy's Free Fall was

supposed to drop two carts in a stomach-churning descent, only to be halted at

the last instant by a gush of hydraulic air. How did one cart come loose like

that? It was tilted just a few feet below the upper platform, as if it had

started downward then changed its mind.

Eddie reached the gate and

had to catch his breath. Dominguez came running and nearly banged into him.

"Listen to me!" Eddie

said, grabbing Dominguez by the shoulders. His grip was so tight, Dominguez made

a pained face. "Listen to me! Who's up there?"

"Willie."

"OK. He must've hit the

emergency stop. That's why the cart is hanging. Get up the ladder and tell

Willie to manually release the safety restraint so those people can get out. OK?

It's on the back of the cart, so you're gonna have to hold him while he

leans out there. OK? Then . . . then, the two of ya's -- the two of ya's

now, not one, you got it? -- the two of ya's get them out! one holds the

other! Got it!? . . . Got it?"

Dominguez nodded quickly.

"Then send that damn cart down so

we can figure out what happened!"

Eddie's head was

pounding. Although his park had been free of any major accidents, he knew the

horror stories of his business. once, in Brighton, a bolt unfastened on a

gondola ride and two people fell to their death. Another time, in Wonderland

Park, a man had tried to walk across a roller coaster track; he fell through and

got stuck beneath his armpits. He was wedged in, screaming, and the cars came

racing toward him and . . . well, that was the worst.

Eddie pushed that from his

mind. There were people all around him now, hands over their mouths, watching

Dominguez climb the ladder. Eddie tried to remember the insides of Freddy's

Free Fall. Engine. Cylinders. Hydraulics. Seals. Cables. How does a cart

come loose? He followed the ride visually, from the four frightened people at

the top, down the towering shaft, and into the base. Engine. Cylinders.

Hydraulics. Seals. Cables . . . .

Dominguez reached the upper

platform. He did as Eddie told him, holding Willie as Willie leaned toward the

back of the cart to release the restraint. one of the female riders lunged for

Willie and nearly pulled him off the platform. The crowd gasped.

"Wait . . ." Eddie said

to himself.

Willie tried again. This

time he popped the safety release.

"Cable . . ." Eddie

mumbled.

The bar lifted and the crowd went "Ahhhhh." The riders were quickly pulled to the platform.

"The cable is unraveling . .

. ."

And Eddie was right. Inside

the base of Freddy's Free Fall, hidden from view, the cable that lifted Cart

No. 2 had, for the last few months, been scraping across a locked pulley.

Because it was locked, the pulley had gradually ripped the cable's steel wires

-- as if husking an ear of corn -- until they were nearly severed. No one

noticed. How could they notice? only someone who had crawled inside the

mechanism would have seen the unlikely cause of the problem.

The pulley was wedged by a

small object that must have fallen through the opening at a most precise moment.

A car key.

"Don't

release the CART!" Eddie yelled. He waved his arms. "HEY! HEEEEY! IT'S THE

CABLE! DON'T RELEASE THE CART! IT'LL SNAP!"

The crowd drowned him out.

It cheered wildly as Willie and Dominguez unloaded the final rider. All four

were safe. They hugged atop the platform.

"DOM! WILLIE!" Eddie

yelled. Someone banged against his waist, knocking his walkie-talkie to the

ground. Eddie bent to get it. Willie went to the controls. He put his finger on

the green button. Eddie looked up.

"NO, NO, NO, DON'T!"

Eddie turned to the crowd.

"GET BACK!"

Chapter

Chapter